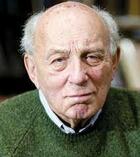

John Lukacs (born Lukács János Albert) is a writer who is dedicated to history. Born in 1924 in Budapest, Lukacs, whose mother was Jewish, managed to escape anti-Semitic persecution in his native country and emigrate to the United States, where he found a haven to think and write. His pen has described the vicissitudes of a good part of the 20th century. A prolific author, his books read like dramas in which the great characters of history unfold his actions as in a Shakespeare play. Owner of a nose for pinpointing the moments in which history is suddenly transformed, Lukacs has taught us that imagination and historical fidelity are not enemies. In his pages, figures like Churchill, Hitler, Stalin or Roosevelt acquire the psychological depth of novel characters without their actions stopping us from telling the adventures of real history. The following interview was conducted at his home in Pennsylvania. The train that connects Penn Station in New York with the town of Paoli did not seem to be full of people interested in knowing the minutiae of the Cold War or the relation of the novel to history. Weeks before and after several phone calls (seven by my count), Hungarian-American historian John Lukacs and this writer made an appointment to meet at a train station in the middle of a Pennsylvania valley. “Our conversation will be a Spanish gathering,” a voice on the other end of the receiver promised me. The word gathering sounded in my ears like fresh water. As the train rolled on, Philadelphia felt like a rumour. Arriving at the station, and as Lukacs had asked me to, I went up the only stairs there were, at the end of which a noble and distinguished figure was already waiting for me. At 89 years old, Lukacs looked healthy. After greeting me, he led me to a car that he himself drove, between streams and winter trees, with the skill of a local taxi driver. Already in the car I confessed to him that on the train I had been reading the book that contains the letters that he exchanged for almost fifty years with George Kennan, one of the mandarins of North American diplomacy. “It's good that you like to read the epistolary genre. It's one of the customs we've lost, like so many others…” The issue of Kennan's longevity came up almost naturally: “Kennan and I were very good friends. He lived 101 years. A life full of adventures but dedicated to thought. You know that next year, if I'm lucky, I'll be ninety." After telling me about his three marriages – “do you know what it is to bury two wives?”, He asked me point-blank; I felt a shudder, but I didn't answer–, he told me that now the only thing he wanted was to be 75 years old again, when he still had the energy to write books and play tennis. I wondered what it would mean to be at the age where one longs to return to the youth of 75.