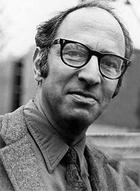

Thomas Samuel Kuhn (Cincinnati, July 18, 1922 - Cambridge, June 17, 1996) was a physicist, historian, and philosopher of American science, known for his contribution to the changing orientation of philosophy and scientific sociology in the decade 1960. Kuhn received his doctorate in physics from Harvard University in 1949 and was in charge of an academic course on the History of Science at the university from 1948 to 1956. After leaving the position, Kuhn taught at the University of California, Berkeley until 1964, at Princeton University until 1979 and at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology until 1991. In 1962, Kuhn published The Structure of Scientific Revolutions, a work in which he presented the evolution of the basic natural sciences in a way that differed substantially from the more generalized view then. According to Kuhn, the sciences do not progress following a uniform process by the application of a hypothetical scientific method. Instead, two different phases of scientific development are verified. At first, there is a broad consensus in the scientific community on how to exploit the progress made in the past in the face of existing problems, thus creating universal solutions that Kuhn called "paradigm". The term "paradigm" designates all the commitments shared by a community of scientists. On the one hand, theorists, ontological, and beliefs and, on the other, those that refer to the application of theory and models of problem solutions. The paradigms are, therefore, something more than a set of axioms (to clarify his notion of paradigm Kuhn invokes the Wittgensteinian notion of the "universes of discourse") [citation needed]. He had some differences with Herbert Blumer mainly because of science and methodologies. Kuhn accepts the focus of symbolic interactionism on actors and their thoughts as well as their actions. The last stage of his thought is tinged by a marked Darwinism. It almost completely abandons the discourse about paradigms, and restricts the concept of scientific revolution to that of a speciation and specialization process by which a scientific discipline limits the margins of its object of study, moving away from the horizons of other specialties. In this last sense, as a restricted form of holism that affects the different branches of scientific development, the concept of theoretical incommensurability reappears, the only one that Kuhn seems to have maintained intact until the end of his days.